My last night at the South Pole I was able to get a tour of the tunnels under the station. As part of the construction of the new station, a tunnel system was created to supply the water and provide a means of sewage disposal. The tunnels are about 30 feet underground.

Here you can see the walls of the tunnel bowing in slightly due to the weight of the snow on top. Eventually they will need to shave the walls. The lights in the tunnel are LED lights which have trouble in the 60 below temperatures. It takes a few minutes of flashing before they warm up enough to stay on constantly.

Here you can see the layout of the tunnel system. The main tunnel corridor is about 3000 feet long I think.

Here is a shot of one of the branches coming off of the main tunnel. Eventually they will put in a rodwell in this tunnel which will supply the water to the station. After they have used up the life of the rodwell they fill the void with sewage.

Here's the helmet that the miners signed. To make the tunnels NSF hired miners from New Mexico and Colorado to use chainsaws to cut blocks of snow out. Workers would then haul the blocks out on sleds. After they went through with chainsaws, the miners used a million dollar machine that had a six foot wide rotating head on the end of a boom that would shave the ice. They would then gradually move the head up and down to make the 10 foot tall tunnel. A system of pipes and holes going to the surface were used to blow the shavings out.

Here is a shot of what the pipe looks like. There two pipes in the tunnels. One supplies water to the station and the other takes the sewage out. They run a heated glycol line next to the water and sewage lines to keep them from freezing.

The tunnel system also houses various shrines that the winterovers make. I think you need to be isolated from civilization for 9 months for many of them to make any sense.

This is a sturgeon that the Russians gave to people in McMurdo. It was eventually thrown away before somebody found it in the trash and it made it's way to the South Pole.

This is looking down the hole in the Rodwell that supplies water to the station. The blue lines were probably about an inch and a half in diameter.

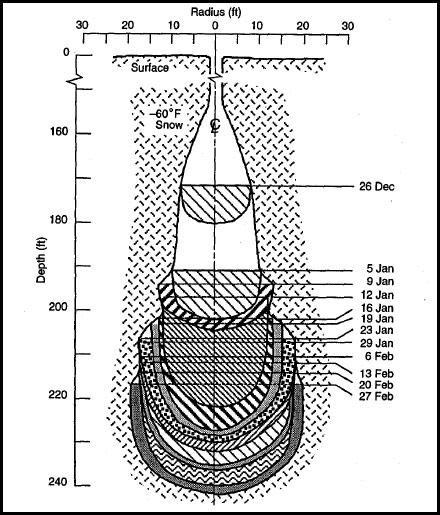

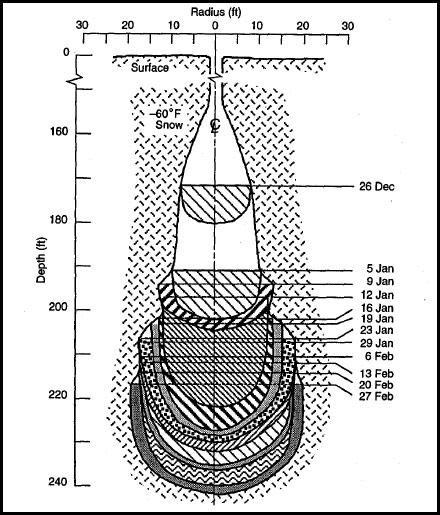

This is a diagram of a rodwell. Basically they use a pump to circulate hot water to make a large bulb in the ice. Eventually they pump so much water out that the rodwell sits hundreds of feet below the surface and it takes so much energy just to get the water out that they start a new one. I guess it takes about 3 years to make a rodwell which then last 7-10 years on average. The bulb may get to about 100 feet in diamter and be about 500 feet deep. After they are done pumping water out they hook up the sewer line and fill it in with sewage which takes about 7-10 years to fill. I was definitely able to tell which tunnel had the active sewer line. I'll add that to my list of Antarctic smells which previously included only diesel.

The air temperature in the tunnels is near constant -60 F. I took this photo at an angle, but the needle was right on -60. In the summer it might seem cold, but it can be 40 degrees warmer than the outside temperature in the winter.

This is a photo of me after the end of the tunnel tour.

We were also able to get a tour of the arches. The arches are all buried structures that house the fuel, supplies, and maintenance facilities for the station. This arch houses all the fuel, about 450,000 gallons I believe. The walls are beginning to bow in places, but it's hard to see in this photo. My camera was having some trouble after the hour or so in the tunnels, so it would work very slowly.

Here you can see the spiral staircase escape in the fuel arch. In the winter, it's a popular staircase to use because it cuts down on the walk outside to one of the buildings. The ice crystals are formed over time from the moisture from exhalations.

Here you can see the indoor food storage. The forklift they have can't reach the top shelf so there is a lot of unused space.

Fuel tank for the generator

One of three generators. They rotate between the engines every few thousand hours of run time. The waste heat from the generators is used to heat water, supply heat for the rodwell, and dry clothes.